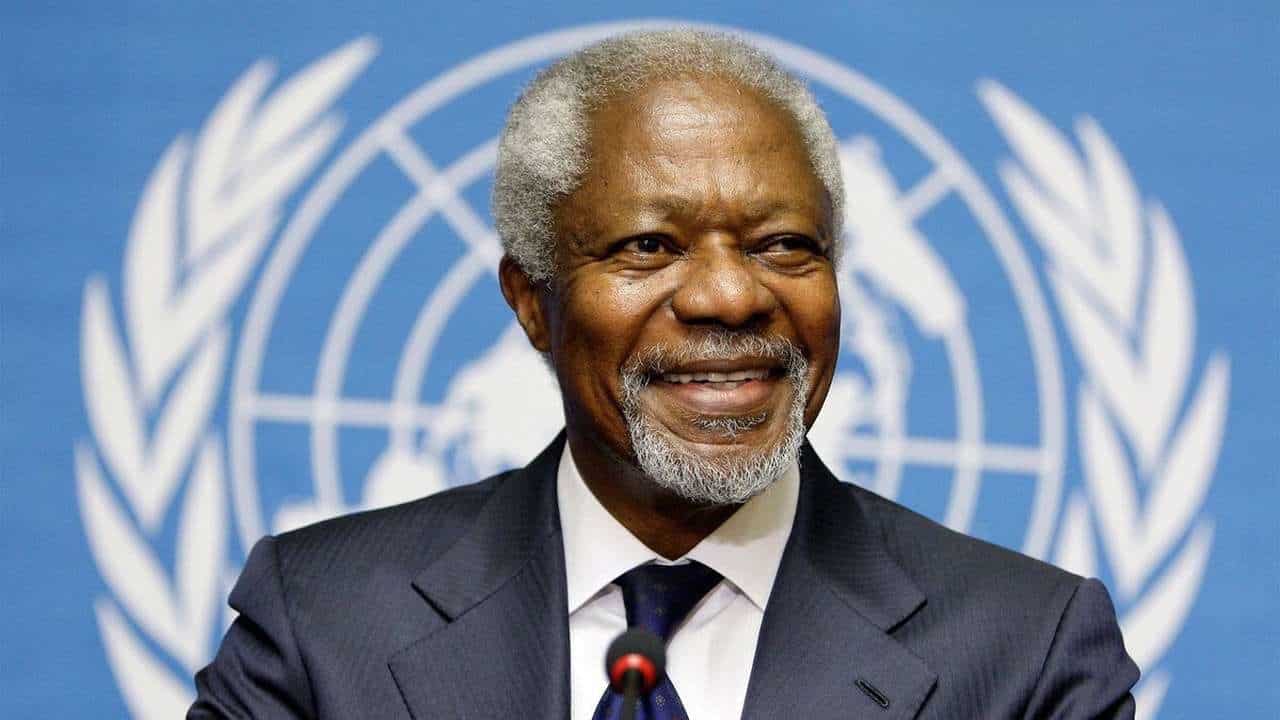

Kofi Annan: Globalization can make the world better

Globalization is a fragile and incomplete experiment, says United Nations secretary-general Kofi Annan. But it can – and must – be a force for good –

More than 50 years ago, a positive vision of world peace and prosperity prevailed among the postwar architects of the global governance system. The United Nations and the Bretton Woods institutions were created in the belief that lasting international peace and economic progress could be built only on solid foundations of international cooperation. Trade and investment were recognized as crucial factors in promoting political and social freedoms and in raising standards of living.

But the postwar economic order that emerged did not just endorse the “magic of the marketplace”. It was also based on a broad consensus that social safety nets and balanced development were every bit as important for stability within and among nations.

Much has changed since then, of course. In 1945 the nation-state was the principal actor in the international arena. Today transnational corporations and civil society organizations have assumed an important role.

Technological revolutions have transformed global communications and transport. Networks of production and finance now span the globe. The boundaries of national economies have been blurred. This openness has come to be known by a single word – “globalization”.

While the expansion of trade and investment has benefited the world economy and helped to alleviate poverty, globalization remains a fragile and incomplete experiment. States feel their sovereignty encroached upon, as so many decisions must take global concerns into account.

Most importantly, billions of people remain excluded from the opportunities of the global marketplace, as half the world’s population must eke out a living on less than $2 a day. Our challenge is to make openness work – to adapt the international system to today’s realities, and to ensure that all people and all countries feel that they have a stake in the system’s success.

The private sector is the primary engine and beneficiary of globalization. Its investment decisions can mean the difference between growth and decline. And its production methods can make the difference between progress and pollution.

Such power cannot be separated from responsibility. The choice is simple: corporations can do more to help reconcile markets with the wider needs of society – they can resolve to be better global corporate citizens – or they can be perceived as part of the problem, with all that this entails.

The Global Compact initiative that I launched in 1999 offers one possible vehicle for responding to this challenge. It asks business to embrace nine universal principles in the areas of human rights, labour standards and the environment, and to enact these principles within their spheres of influence.

I picked these areas because I was worried by a severe imbalance in global rule-making: while there are extensive and enforceable rules for economic priorities such as intellectual property rights, there are few strong measures for these other concerns, which have such a direct impact on human welfare.

Originally intended as a call to action, today the compact involves not only business but also labour federations and nongovernmental organizations.

They are finding it a useful platform for building consensus on important social and environmental issues, for initiating joint projects on the ground, and for bringing universal principles into boardrooms.

Business leaders have already shown that there is much they can do within their spheres of influence, on their own or with the compact in mind. Here are some examples.

HIV/Aids

Volkswagen in Brazil and DaimlerChrysler in South Africa have introduced expanded “AIDS Care” programmes.

Corporate culture

Companies such as Novartis, Pearson and Spedpol have incorporated the compact’s principles into employees’ job responsibilities and criteria of success throughout their worldwide operations.

Labour relations

Statoil, Telefónica and other companies have used the compact’s principles to reach global framework agreements that assure their workers fundamental rights and principles at work.

Tolerance

Volvo and five other companies are combating discrimination and promoting diversity with a joint report and awareness campaign, “Discrimination is Everybody’s Business”.

Environment

BP has set a new standard with its internal emissions trading system, reducing greenhouse gases, and STMicroelectronics is well along the path of developing environmentally friendly products.

These and other company-led initiatives and projects are more than micro solutions. They set new examples and, by inspiring others to do likewise, they can bring about systemic change. But many issues can be tackled only if different actors join forces. Through its learning and dialogue forums, the compact offers a platform for this as follows.

Poverty

The compact has led to dozens of partnership projects in developing countries, addressing issues such as access to water and energy, health care, education and job training.

Transparency

Companies, trade unions and NGOs have developed a platform for action to break the cycle of corruption and to foster transparency and good governance.

Conflict zones

Companies and NGOs have developed guides, now being field-tested, which aim to ensure that business activities do not aggravate conflict but support efforts towards peace and reconciliation.

Least developed countries

More than 30 companies, labour and civil society organizations have teamed up to promote investment, overcoming economic and social barriers that might have prevented it.

None of this is meant as a substitute for action by governments, or as a regulatory framework or code of conduct. Rather, the compact is a voluntary initiative, a platform for showing how markets can be made to serve the needs of society as a whole.

Businesses might ask why they should go down this path, especially if it involves taking steps that their competitors might not.

The answer is that, sometimes, doing what is right – for example, through eco-efficiency or creating decent workplace conditions – is in the immediate interest of business. Sometimes we must do what is right simply because not to do so would be wrong. And sometimes we do what is right to help usher in a new day of new norms and new behaviours.

The compact’s work for responsible global corporate citizenship is but one response to the challenge of making openness work. Together, we can and must move from value to values, from shareholders to stakeholders, and from balance sheets to balanced development.

Only then will we fill the voids and gaps in global governance. And only then will we shape globalization so that its benefits are more widely shared, and place development on a more sustainable footing.

For that we shall need leadership. For that we must all be willing to take global cooperation to a new level.

Kofi Annan is secretary-general of the United Nations. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2001.